I. Foreword: An Exhibition Based on a Publication

This exhibition belongs to those that I would pursue with many costs to whichever place reachable to me: it has a clear argument to make about an issue as big as our shared human experience, it brings forth a large number of valuable artifacts, and its argument and ways of storytelling might very much be provocative, even more, if the exhibition is to be seen against the general social and cultural environment where the exhibition is hosted. Therefore, here I am in Shanghai on the first day of September.

Actually, before my departure, I also planned to visit another museum. A temporary exhibition hosted by a regional museum on the periphery of Shanghai, named “A Story of Lanting,” seemed to have fascinated me. Its name, though attractive enough for art-lovers and cultivated humanists, sounded familiar to me, and after suspiciously browsing through my bookshelves, I found a book bearing the exact same title: A Story of Lanting. Not only did the exhibition borrow the entire storyline, but it also put much detailed evidence into the glass display as well, with no essential difference at all! I immediately scoffed at this idea of carrying off a published work and bringing it into exhibition rooms: wouldn’t it be so easy for museum curators to design exhibitions based almost exclusively on studies of art history, a complete lack of creativity! Having also known that significant artifacts central to the exhibition are all replicas of their originals, I eventually gave up on that exhibition.

Well, on second thought, I reminded myself that “A History of the World in 100 Objects” is also an exhibition of that nature.

Indeed, it is, the fame of both this title “A History of the World in 100 Objects” and the idea of retelling human history through objects owes exclusively to a set of well-renowned and widely read books by former British Museum director Neil MacGregor, A History of the World in 100 Objects, which is further based on a radio program by both the Museum and BBC. What, then, besides the thrill of seeing 100 pieces of a national treasure in their originals, remain as reasons for seeing such an exhibition carried off from publications from more than seven years ago?

Fortunately, after my visit, I felt that this exhibition was not quite a “faithful copy” of that book. Only about one-fourth of the original one hundred objects mentioned in the book made their way to Shanghai, while the rest consisted of other artifacts of curators’ choice from the British Museum. Besides practical reasons, at least three fourth of the exhibition would reflect how current curators attempt to accomplish the task of reconstructing human history in the way the book successfully does. What’s more, this exhibition took on a very different form. A book or radio program can present all 100 objects with an equal emphasis by having individual chapters or episodes and each bearing a distinctive argument; a museum exhibition cannot. The latter must be highly coherent, highlighting some over others and showcasing a few as epitomic examples while reducing others to supporting pieces of evidence. An exhibition also has to balance visitors’ sensual experience with their acquisition of knowledge. Eventually, all those differences in forms and concerns were to be reflected in the choices of the remaining three fourth of display objects and in ways in which all artifacts showcase the multifaceted human past and present, thus making this exhibition rather “unfaithful” to what we already have as book or radio program. Although based significantly on a published work, “A History of the World in 100 Objects” was, in many ways, an exhibition on its own.

There can be good and bad “plagiarism” after all!

II. An Attempt to Retell Human History

As the director of the British Museum, Dr. Hartwig Fischer said in his foreword to this exhibition, in an effort to reexamine human history through interpreting material evidence, “A History of the World in 100 Objects demonstrates that human beings in all times and places confront the same problems, and share the same aspirations.” The legitimacy of this argument must be contemplated with a view to the following questions: in what way does this exhibition propose that material evidence shall be interpreted, in what way does it weave together all interpretations to present a consistent and coherent human history, and in what way does such presentation of human history work in the way this exhibition proposes?

As for the first question concerning how material evidence shall be interpreted, this exhibition, unfortunately, answered almost nothing. Dr. Fischer gives his visitors great expectation of learning how to read exciting stories out of even “the most humble objects.”

“This exhibition … highlights the remarkable stories which can be revealed through even the most humble objects. … All of these objects come together to tell a global story that spans continents and millennia.”

But instead of showing how, the exhibition is overloaded with telling what those exciting stories are. Placards of each section would generalize what kinds of human achievements are to be expected in certain historical moments, and those on individual items mostly offer stories. Only a scanty few hinge on the process in which scholars came to the knowledge of those stories: how do we know those that we have known? Among the few, one particular part about the Shepenmehyt inner coffin is worthy of mentioning. Very problematic is its emphasis on the role of medical analysis in interpreting somehow organic objects such as this coffin and mummy, as though technology takes the lead in interpreting material evidence. This is a dangerous assumption for visitors to make, which is further necessitated by the void of showing the cultural and societal importance of this coffin. Telling imprecise things is even more harmful than keeping silent. Even if visitors are lucky enough to omit that idea, they end up hearing only a wonderful collection of stories, regardless of whether they argue for anything or not and eventually forgetting almost everything. Because we are very Spartan in receiving information; we are of poor memories. In one way, understanding “how” is one step deeper than understanding “what,” and in another, remembering the essential “how” is easier than remembering a lot of “what.”

As for the second question concerning how this exhibition presents human history, this exhibition does a very good job of keeping a balance geographically, diachronically, and thematically. It manages to show marks of human existence and traces of human flourishing “in all times and places” through objects. Selected objects have very strong representative power of their regional culture in certain historical periods. Furthermore, within a chronological sub-division, many aspects of human life are explored: political and military power, spiritual and religious devotion, household issues, recreational attempts, and so forth. This exhibition backs up its universal claim of “people in all times and places” very well by means of its objects on display.

As for the third question, namely what ideas stand behind such narration of human history, it seems to me, from the ways in which objects are interpreted and stories are told, that this exhibition promotes three general claims of humanity as its assumptions which make its initial argument possible. Firstly, human history is a process of encounters and communication. From the very beginning when the Olduvai Hand-axe was considered to be the Swiss army knife of ancient travelers, to the very present day where a single counterfeit Drogba jersey could reflect interactions between all continents, this exhibition seems to propose that the making of our globalized modern society is largely due to the invariable human desire to meet and exchange. However people meet each other and whatever people exchange, they are bound to discover the universality of human history.

Secondly, the universality of human history either is caused by or gives rise to some shared values of human societies. People migrate, empires expand, and thoughts and ideas are spread around … The exhibition seems to show an outward movement of every element of human life that very much reflects an expansionist view of history. Human beings, motivated by their insatiable desire/curiosity, are always looking out into the unknown and seeking to make the unknown known. In the meantime, clash or cooperation gradually bound human beings into one community, and such is the come-about of our modern world. This process, moreover, leads to the understanding of the last assumption. Human beings value progress, and although human beings might confront different problems at different points, they always “share the same aspirations.” Human societies essentially strive for prosperity, and such a process is always a process of making progress. We human beings are always on the same page, though troubled by the same crisis, yet always hoping for achieving the best.

Such are the fundamental ideas behind the exhibition to my understanding, and problematic as they are, they also make some very good cases. However, I would still say that under those assumptions, some civilizations could never be fully understood, such as Sparta, which was the most stagnant with respect to progress and almost had no spirit of expansionism at all, and such as China, whose interactions with its neighboring sovereign states as well as ethnic groups throughout its history were much more complicated. Those assumptions are biased towards those who are proactive in stirring up the world. After all, it is not meant to question those assumptions if one were to understand this exhibition, for, without a common ground, a good conversation between visitors and this exhibition could not be possible.

III. A World History for Chinese Audience

Having said much about this exhibition itself, I will now turn to its audience – the recipients of ideas, stories, and values of human history proposed by the exhibition. Always, there lie the questions of what visitors have known prior to their visit, what they want to know, and eventually, what they should know after their visit. Moreover, given all that has been done by the curators, in what aspects can we, visitors to this exhibition, potentially benefit from it?

Firstly, who are “we?” During the past three years, “A History of the World in 100 Objects” has been touring around East Asia first in Taipei (2014 – 2015), then in Tokyo (2015), in Beijing (March to May 2017), and eventually in Shanghai (July to October 2017). Although the British Museum has made some minor changes in the choice of 100 objects, the spine of this exhibition remains the same. It seems reasonable to conclude that this exhibition targets a general audience of East Asian spectators.

How those curators cater to the “wants” and “expectations” of East Asian visitors, and more specifically, Chinese visitors in Shanghai, is extremely subtle. First of all, seeing familiar things would naturally attract the attention of visitors – they know them! One can see a big amount of East Asian artifacts on display – North Korean artifacts, Chinese jade bronze, and porcelain ware, Japanese lacquer pot – and indeed, people were thrilled when fixing their gaze on the gigantic, well glazed, and painted Yuan porcelain plate, and astonished to know that our neighbor Japan has preserved its pre-history up to 20,000 years ago. On the other hand, the exhibition managed well in regulating an appropriate number of those objects, so as not to limit our perception of “world history.” But this strategy of sampling objects culturally familiar to us meets its success.

A more important concern, possibly having been very carefully evaluated by Chinese curators, is the question of what aspects of world history, besides their native cultures, visitors are fascinated with. The way most of us usually see an exhibition is such that based on our background knowledge shaped by a prevalent Chinese perception of world history, either by means of education or other mainstream sources of information, we contemplate and cast judgment on ideas proposed by the exhibition. I am only suggesting the existence of a common view of this exhibition unconsciously possessed by the majority of visitors which is deeply shaped by societal values. To take one case as an example, from my observation either in bookstores or at museums, Chinese people are deeply fascinated by ancient history, probably because we proudly possess one of our own. On the other hand, we Chinese have little knowledge of the world concerning what lies beyond the influence of western civilizations. “What was the rest of the world doing 6000 years ago when we are having our jade and ceramic culture, and do other cultures have equally flourishing prehistorical societies as we do?” “What forms of power structure do the African cultures have, and are there ethnographies about pre-Islamic Arabia?” We might ask, thus or in similar ways.

Accordingly, this exhibition satisfied our curiosity, and specifically put on display objects of distant cultures that are easy for us to relate to a chopping tool from Africa, a cosmetic palette from pre-dynastic Egypt, a spearhead from America, a bust of an ancient Greek tragic poet, a bronze hand that signifies the existence of Arabic local religions, and so on. “Wow! We have never known the might of the Benin empire, and nor do we know about those Oceanians! Llamas, besides the fact that they are cute and they spit, were both utilized as means of transportation and venerated as sacred animals by the Incans!” The answers to our questions are by no means systematic; nor are they supposed to be thorough. How specific objects tell a story insightful enough to shed light on the whole culture is the tantamount concern of this exhibition. In a word, curators of “A History of the World in 100 Objects” are simply opening up windows for visitors, through which magnificent lights shine in all directions from the distant human past. While some are delighted by those shining lights, others, if observant enough, are able to make out the common source of those lights, which this exhibition proposes to be a single motivating force behind our universal history – humanity.

IV. Epilogue: The 101st Object

What could be a better way to conclude this exhibition than having each museum design the last – 101st – object of this interesting history of the world?

This is the practice that all museums that have hosted “A History of the World in 100 Objects” have agreed upon with the British Museum to put one more object as the last note of history and show its continuation into our present and future. Particularly, Beijing National Historical Museum kept the 101st object as the only top-secret of this exhibition – a secret that you can only come and see for yourself. All of a sudden, speculations of all sorts came about: “what, among the countless national treasures housed in the National Museum, could possibly become the 101st object on display? Is it going to be a piece signifying high art from the past? Modern art produced by those 798 artists? A thing from daily life?” It is especially astounding that no one among the visitors had spoiled the secret on the internet while the exhibition was going on! I myself, not being able to go in the flesh, still made a huge effort to learn about this 101st piece three months after its closure in Beijing.

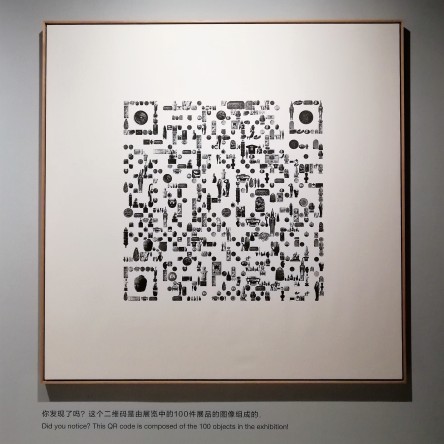

By comparison, Shanghai Museum did not keep this a secret at all. Perhaps they don’t even see this as a secret. Altogether with other information about this exhibition, they proudly announced what their 101st object was going to be even before this exhibition officially opened. I thought to myself after my visit how wonderful my experience will be if the Shanghai Museum’s 101st object struck me as a complete surprise! For, it suits very well what this exhibition has been primarily proposing: telling what is happening in societies using the most humble objects.

This is the 101st object of “A History of the World in 100 Objects” in the Shanghai Museum: a large QR Code at a glimpse, but if looking close enough, one can find out that the black-and-white of this figure is made up of all 100 objects on display. QR Code, which stands for Quick Recognition Code, was first invented by a Japanese corporation in the 1990s so that scanners of those codes can quickly recognize them and retrieve the information. But whoever has been in China recently knows how prevalent those QR Codes are – they are everywhere! A short video shows how QR Codes permeate every aspect of daily life: yes, people still scan codes to retrieve information, but no longer about mechanical parts like how the Japanese corporation did initially. Nowadays, Chinese people pay by scanning each others’ QR Codes, they add each other on social media, they follow blogs and pages, and they download applications by scanning QR Codes. Scanning QR Codes signifies a change in our ways of establishing social connections and shows how modern Chinese people encounter and communicate with each other.

As for how QR Codes function, this exhibit of a QR Code can, to my great surprise, be scanned to get information! As I was excited to guess what type of things could pop out on my phone, I was already directed to a very special “online placard” of this exhibition: an introduction to QR Codes, how they work, what their advantages of establishing social networks are, and how a QR Code exemplifies our society in the present day. As people were drawn to the magic of QR Codes and this object itself, I began to marvel at the subtlety of this design. By letting interested visitors scan this Code comprised of all 100 objects that profoundly shaped our ways of communication in history (as we have said, communication is a big theme), this exhibition again leads people to interact with human history and, most of all, with the modern society, using the newest way of defining social relations. And again, in retrospection, when looking at the “Swiss army knife” of prehistoric travelers, for instance, we marvel again at how material evidence bears witness to our course of human development.

On this exhilaratingly high pitch, this exhibition comes to an end. With pros and cons, I am truly grateful for having the opportunity to enter into a conversation with this exhibition which is equipped with the best exhibits, is supported by the most creative curators, and raises the most provocative voices and most meaningful questions.

Philomuseia

2-9-17 drafted in Shanghai, China

4-9-17 revised in Beijing

10-9-17 revised again in Northfield, MN

Cover image: Shanghai Museum at dusk.